It’s certainly not a traditional starting place for research, but when it comes to studying nineteenth- and early-twentieth-century America, www.ancestry.com is an indispensable resource. In studying singers who performed opera in the American Old West, it has supplied me with documents including ship manifests, birth and death records, censuses, and wills and testaments. Such sources often confirm or refute anecdotal evidence that has become lore, provide new insights, and if the individual you’re studying happens to have living descendants, it’s not uncommon to benefit from the hard work of family genealogists. And all of this is available in one place, for the low monthly fee of $19.99. The “Shoebox” feature lets you easily save documents or lines of documents needed for reference, you can easily search adjacent or linked names in records, and each item is thoroughly documented in terms of its original source, roll, page number, etc. Throughout this short excerpt from my dissertation, * denotes the presence of a footnote whose source is www.Ancestry.com.

To see www.Ancestry.com in action, let’s take, for example, the Italian-American soprano Carlotta Patti (1835*–1889). She’s the elder sister of the much more famous Patti—the “Queen of Hearts” soprano Adelina Patti. She was herself a talented singer, and an admired member of one of America’s great dynasties of performers. Unfortunately, she’s never received the attention she deserves from historians of any stripe. John Frederick Cone, in his biography of Adelina Patti from 1993, grants Carlotta a mere two sentences, and selectively underscores a physical handicap—a limp caused by a congenital disorder or horse-riding accident, depending on which story of hers we are to believe—as the cause for her not having a more prosperous career on the opera stage. But in point of fact, Carlotta Patti did have a career that many singers would (and still do) aspire to, even if it consisted mostly of recitals and solo concerts, accompanied by some of the most esteemed musicians of the day—from pianist Louis Moreau Gottschalk to her husband, the cellist Ernest de Munck. By considering her career as “less than” Adelina’s, scholars have disregarded the contributions she made to democratizing and disseminating art music in nineteenth-century America.

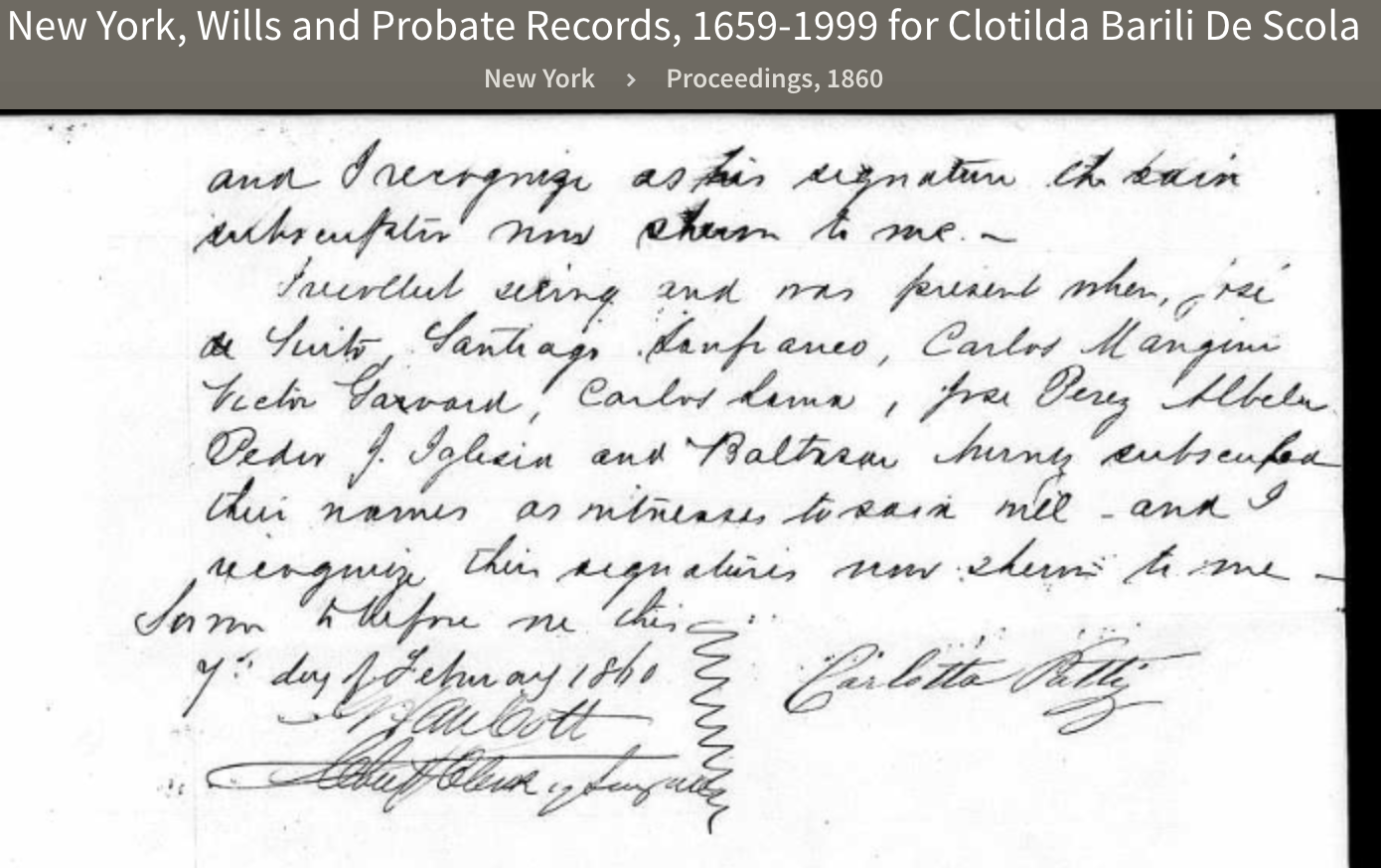

Carlotta Patti was born in Florence in 1835, the second child of tenor Salvatore Patti and soprano Caterina Chiesa Barili-Patti.* As is well-documented, the family arrived in New York in 1846, and Salvatore established, along with buffo Antonio Sanquirico, an Italian company at Palmo’s Opera House. Carlotta took up piano studies under Henri Herz, the famed Austrian virtuoso and pedagogue, who taught and performed in the United States between 1845 and 1851.* In 1852, the eldest daughter of Salvatore and Caterina, mezzo-soprano Amalia Patti, married impresario Maurice Strakosch, a decision that was expedient for establishing the Patti name. As recorded by Adelina’s biographers, Carlotta advanced as a pianist and subsequently taught her younger sister piano. That is, before her own aspirations as a concert artist were put on hold. Carlotta traveled to the West Indies and South America in 1856* to care for an ailing elder half-sister, Clotilde, from her mother’s first marriage to the composer Francesco Barili.* According to Carlotta’s own testimony given during probate proceedings regarding Clotilde’s last will and testament, she was in Lima, Peru in April 1857, shortly before returning to New York from Panama on 14 May 1857.*

Rivalry between Carlotta and Adelina could only be expected when she returned, and it may have been on this account that Carlotta found herself pursuing a singing career. While Carlotta had been away, Adelina met great success on a tour of the West Indies with Gottschalk, performing in Havana just weeks before her half-sister’s (Clotilde) death in March 1858.* Carlotta, instead of resuming her study of piano, set to training her voice. Her training was likely carried out partly under the tutelage of Clotilde’s husband, Carlo Scola, who had returned to New York with Maurice Strakosch in September 1859 with a new band of Italian opera singers in tow, and was indebted to Carlotta for her care of his ailing wife.* Adelina spent the better part of the spring and summer of 1860 on a tour through eastern cities and as far west as Chicago with Amalia, tenor Pasquale Brignoli, Strakosch at the piano, and others.

Gothamites were missing their homegrown prima donna, and in little time began to look for a replacement. The first and most evident option was Carlotta, the New York Times issuing this statement in early June, when Adelina was in Cincinnati: “Miss Patti’s sister, Miss Carlotta Patti, highly esteemed by all the connoisseur-world of New-York as a pianist and a vocalist of the first force, has been invited to atone to her sister’s admirers, for her sister’s absence by a concert, with which request she will shortly comply.” Operagoers, finished with feeling unappreciated by their leading prima donna, sought penance from some member of the Patti family. Carlotta’s solo concert debut took place at Dodworth’s Saloon on October 25, 1860. Dodworth’s was a gentlemen’s concert room opened by the band master Harvey Dodworth in 1858*, a much different venue than the Academy of Music where Adelina had performed exclusively of late. However, as David Monod has shown, pre-Civil War concert saloons did not fit the stereotype of “disreputable dives where working-class men went for rough entertainment, sexual encounters, and cheap liquor.” Rather, Dodworth’s regularly featured opera singers, along with other types of “high” entertainment or the like in adaptations, expanding the accessibility of opera beyond the opera house. Operas were truncated, interspersed with performances by acrobats and comedians, and integrated within an evening of general pleasure and amusement. It was after these New York gentlemen’s saloons and their variety of entertainment that opera houses in the West were fashioned, where Carlotta Patti indoctrinated a generation of immigrants, miners, and sourdoughs into admiring opera and star singers.

—Austin Stewart

Austin Stewart is a sixth-year doctoral candidate, researching opera and civic identity in the American West during the nineteenth century, with an emphasis on the theatres, performances, and artists encountered by the citizens of Denver. His dissertation committee is chaired by Prof. Mark Clague.

Recent Posts

SMR to Host Midwest Graduate Music Consortium 2025 Conference – January 13, 2025

SMR Welcome BBQ at County Farm Park – October 01, 2024

Julian Grey defends dissertation – June 05, 2024

Michaela Franzen defends dissertation – May 21, 2024

Kai West defends dissertation – May 16, 2024

Micah Mooney and Carlos Pérez Tabares present at Music Theory Midwest – May 12, 2024

SMR end-of-year round-up at County Farm Park – April 25, 2024

SMR hosts Research Showcase – September 29, 2023

Society for Music Research

Society for Music Research