Recently, several SMR members were involved in events surrounding the premiere of a new edition of George Gershwin’s Porgy and Bess, part of U-M’s Gershwin Initiative. One of the main events of this Gershwin-packed weekend was a two-day symposium devoted to discussions of race, representation, activism, and appropriation in the opera. Two current SMR members gave papers: Lena Leson gave a paper entitled, “‘I’m On My Way to a Heav’nly Lan’’: Porgy and Bess and American Religious Export to the USSR,” and Austin Stewart, gave a paper entitled, “Taste and Adaptability”: An Examination of Opera and Racial Uplift” (abstracts below). In addition, U-M alumnus Andrew Kohler also presented a paper, while Gershwin Initiative Managing Director and U-M alumna Jessica Getman co-organized the symposium and participated in both a lecture and a panel discussion. The keynote talk, entitled “Too Decent to Understan’”: Witnessin’ Musical Appropriation from the Traditionally Broken-Hearted,” was given by Kyra Gaunt, another U-M alumna. The symposium and the performance that followed were by all accounts a resounding success. Congratulations, all!

Lena Leson and Austin Stewart presented papers as part of the symposium.

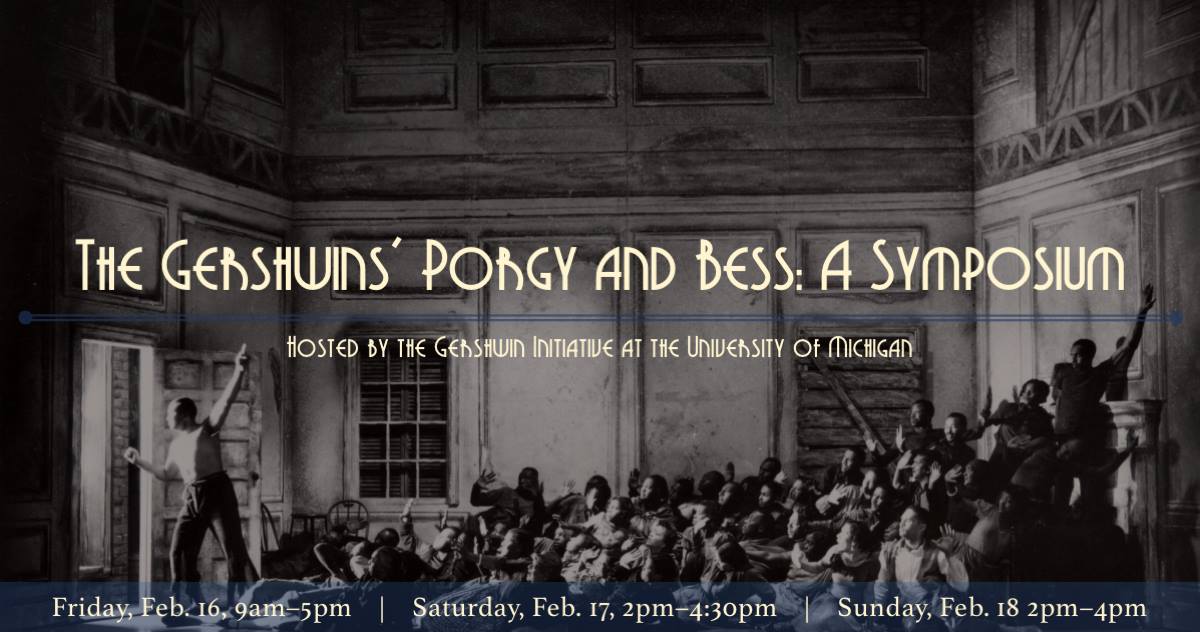

Image credit: U-M's Gershwin Initiative. Photo credit: Mark Clague.

“I’m On My Way to a Heav’nly Lan’”: Porgy and Bess and American Religious Export to the USSR (Lena Leson)

When Helen Thigpen and Earl Jackson, singers in Robert Breen and Blevins Davis’s mid-1950s production of Porgy and Bess, married in a Moscow church on January 17, 1956, the whole world seemed to be watching. Both American and Soviet press covered the Baptist service, and more than 2,500 Muscovites crammed into and waited outside the church where the celebrity couple was joined in holy matrimony. Photos of the wedding in Life magazine’s full-page feature highlighted the socio-economic difference between the glamorous stars of Porgy and Bess and Moscow’s bundled babushkas, suggesting not only the rising status of African Americans in the US, but abuse of the faithful in the Soviet Union. Religious belief had become a weapon of Cold War propaganda.

An early example of the kind of exchange that would define much of the cultural conflict between the United States and Russia during the Cold War, scholars have explored the use of Breen–Davis’s Porgy and Bess and its stellar ensemble cast to counter Soviet criticism of US race relations. But while race was paramount in State Department memos regarding the Soviet tour of Porgy and Bess, faith was an equally prominent theme in contemporary coverage of the production. Drawing on materials from the Robert Breen Collection, housed in The Jerome Lawrence and Robert Lee Theatre Research Institute at The Ohio State University, this paper reexamines the mid-century exportation of Porgy and Bess as a critique of the Soviet Union’s state atheism and anti-religious attitudes.

Onstage as well as off, Porgy symbolized American piety, echoing President Truman’s assertion that democracy’s most powerful weapon against the godless Soviet enemy was neither a gun nor a bomb, but faith. My research, which considers Breen–Davis’s Porgy and Bess as a religious export to the USSR, aims to enrich our understanding of US cultural diplomacy and Cold War-era exchange with broader implications for American–Soviet history, religious studies, and opera analysis.

“Taste and Adaptability”: An Examination of Opera and Racial Uplift (Austin Stewart)

The nineteenth-century African American experience in lyric theatre was initially limited by and respondent to blackface minstrelsy. For some black American musicians, comedians, actors, and singers, portraying the stereotyped characters in the popular genre offered a point of entry for a career on stage. Over time, these artists began to cultivate their own celebrity, and the novelty of hearing black singers in genres other than minstrelsy presented new (albeit infrequent) prospects. The distance between opera and minstrelsy was not as great as it might seem today; both were mainstream entertainments, performed by traveling troupes across the country, and marketed to middle-class audiences. During Reconstruction, African American musicians began to redress the relationship between these two forms of theatre. Some integrated vernacular musical traditions, minstrelsy, and opera in original works that celebrated blackness. Others rejected these traditions in an effort to create a “school” of black opera, legitimized by its similarities to European opera and its liberation from minstrelsy.

In the first place, I consider the Hyers Sisters’ ballad opera Out of Bondage, which endeavored to legitimize operatic performance by African Americans by ensconcing it within genres that did permit them authorship; in the latter, I consider the first of many attempts made by Harry Lawrence Freeman to ingratiate the operatic art to black intellectuals. In both cases, we find that these artists used opera to tell stories that were theirs, not the fictions that were put upon them.

Recent Posts

SMR to Host Midwest Graduate Music Consortium 2025 Conference – January 13, 2025

SMR Welcome BBQ at County Farm Park – October 01, 2024

Julian Grey defends dissertation – June 05, 2024

Michaela Franzen defends dissertation – May 21, 2024

Kai West defends dissertation – May 16, 2024

Micah Mooney and Carlos Pérez Tabares present at Music Theory Midwest – May 12, 2024

SMR end-of-year round-up at County Farm Park – April 25, 2024

SMR hosts Research Showcase – September 29, 2023

Society for Music Research

Society for Music Research