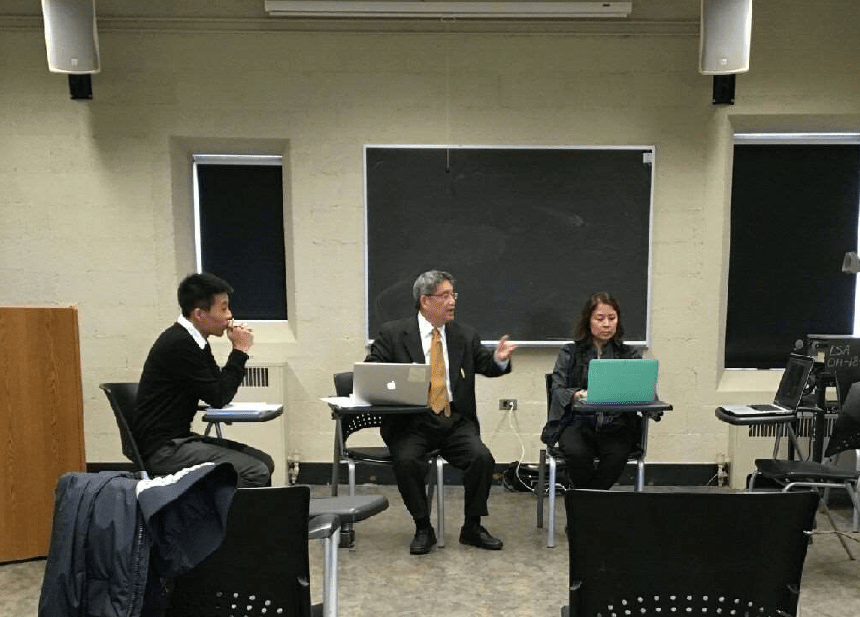

Last week, ethnomusicologist Ho Chak Law successfully defended his dissertation, entitled “Cinematizing Chinese Opera, Performing Chinese Identities, 1945-1971” (abstract below), before a crowd of distinguished guests. Congratulations, Ho Chak! We’re proud of you, but sorry to have you leave us!

Abstract

On stage and on film, Chinese opera persisted in being an important means of articulating Chinese identities during the mid twentieth century, a turbulent period in modern Chinese history. In this light, this dissertation investigates how Chinese opera on film illuminated the moments when cinematic technology deterritorialized the circulation of cultural and musical meanings within and beyond traditional contexts. I argue that in similar temporalities but under disparate political regimes, Chinese people in Mainland China, Taiwan, Hong Kong, and Southeast Asia deployed Chinese opera to cinematize Chineseness.

My investigation consists of three parts. In part one, I first reveal that in the existing scholarly literature on Chinese cinema, there are notable tendencies to conceive of Chinese opera as the national essence. I then give nuance to such tendencies by illustrating Chinese opera as an evolving system of key symbols that, despite being mediated by cinematic technology, retained various longstanding discourses and practices for the construction and renewal of national subjectivities among Chinese people. I highlight how Chinese opera was entangled in Chinese cinema’s critical and ontological discourses as a performing art and a cultural form. In part two, I demonstrate how The Butterfly Lovers migrated from stage to cinema and became Liang Shanbo and Zhu Yingtai (1953) and The Love Eterne (1963), such that a Chinese traditional story par excellence was subject to both hegemonic and counter-hegemonic articulations of Chineseness, without losing touch with Chinese opera’s representational idiom and performance conventions. In part three, I use The Sorrowful Lute (1957) to exemplify how, as cultural critique, film remaking could prompt Chinese people to use their social and experiential knowledge of Chinese opera to negotiate the Chinese self against the Western other. Overall, I posit that Chinese opera on film manifested the evolvement of Chinese nationalism from a top-down ideological construct masterminded by politicians and intellectuals, into a strongly contested undertaking of identity formation that involved members of all social strata.

Photo credits: Nee Chucherdwatanasak, Steve Lett, William van Geest

Recent Posts

SMR to Host Midwest Graduate Music Consortium 2025 Conference – January 13, 2025

SMR Welcome BBQ at County Farm Park – October 01, 2024

Julian Grey defends dissertation – June 05, 2024

Michaela Franzen defends dissertation – May 21, 2024

Kai West defends dissertation – May 16, 2024

Micah Mooney and Carlos Pérez Tabares present at Music Theory Midwest – May 12, 2024

SMR end-of-year round-up at County Farm Park – April 25, 2024

SMR hosts Research Showcase – September 29, 2023

Society for Music Research

Society for Music Research